The last time I went to visit your grave was two years ago. That Michigan summer was cool and rainy, the evening overcast and humid. I drove alone to the cemetery with a potted plant to place beside your headstone. But when I got out of the car I was greeted by a thick cloud of mosquitoes. Even through my jacket and leggings I could feel their stings. Frustrated, I turned around and dashed back into the car. I stared at the plot from my window for a few minutes before I turned the key in the ignition and drove away slowly.

Dad got married that summer. Jacob got married later that fall. We went home at Christmas but I didn’t come back to your graveside then either. It was a long time before I went home again. I said it was because we were trying to save money, and because we had too many other obligations. It’s not untrue, it’s just not the only truth.

The truth is you can never go home again.

//

It’s a breezy morning in April when I finally come back. The Monday after Easter. It’s my first trip home in a long time. We don’t stay in the house where I grew up. We don’t have the same big family gathering for holidays anymore. There are different places and new people and a whole life that we never imagined living when you left us, most of it good but all of it bittersweet.

I plant a tulip beside you.

The tears I thought weren’t there are on my cheeks suddenly, as if they never left me.

I am not fine.

I am fine.

The thing I thought would eat me alive has not, but I feel every tiny sting.

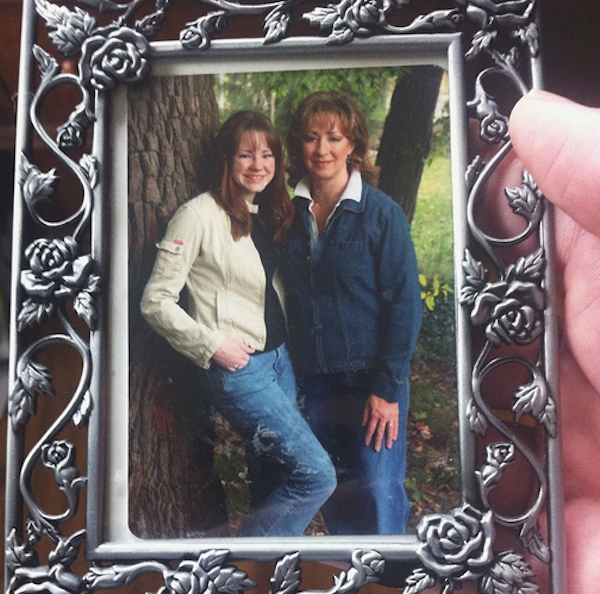

I come to you a version of myself that I’m not sure either of us recognize, but I’m all me just the same.

Hi, Mom. I missed you.